Justice officials launch another investigation of DEA payments to informants

The Department of Justice’s Office of the Inspector General is investigating how the DEA manages and oversees informant payments, which are a controversial law enforcement tool.

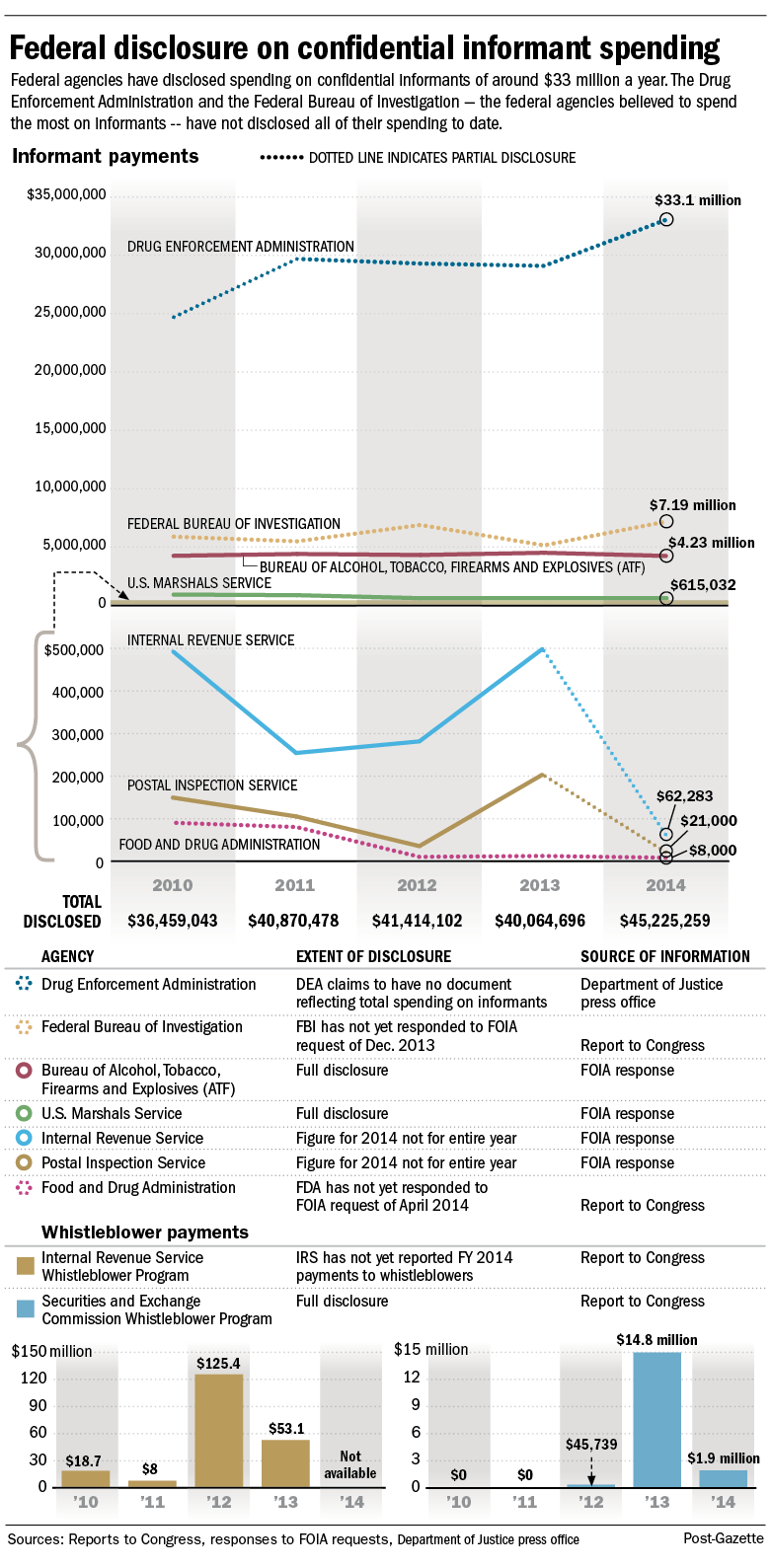

The DEA’s spending on secret sources has increased much faster than its overall budget. Last week, the Justice Department , which oversees the DEA, released to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette the agency’s total payments to informants for each of the past five fiscal years.

The disclosure came 15 months after the newspaper made Freedom of Information Act requests for documents totaling and detailing its spending on informants since 2010. The DEA’s repeated denials suggest that it has trouble tracking the dollars it dishes to informants, a decade after inspectors told it to fix its payment database.

That’s despite increasing payments to informants, which totaled $146 million over five years.

“I have to say I’m kind of shocked” by the volume of payments, said JaneAnne Murray, a federal criminal defense lawyer and practitioner in residence at the University of Minnesota Law School.

She said informants angling for lenient sentences are usually revealed to the defense, but paid sources remain in the shadows except in the rare federal cases that go to trial. As a result, the truthfulness and credibility of paid sources are rarely tested.

The dollar figures, she said, are “pretty troubling, because once you start introducing a profit motive, there’s a huge potential for fabrication.”

Justice Department spokesman Wyn Hornbuckle noted that payments to informants are “based upon the value of information or services provided.” The department’s guidelines to the DEA, FBI and other bureaus are meant to avoid inappropriate use of paid informants.

‘Lax controls’

Federal law enforcement depends on thousands of informants. Some are criminals, cooperating in the hopes of probation or shorter prison terms. Others are paid.

The Post-Gazette last year documented the appearances in the U.S. Courthouse, Downtown, of informants with decades of experience who received upward of $30,000 per bust. The newspaper also found that of nine acquittals in the courthouse over six years, four involved shaky informants — none of whom were paid and all of whom dealt with the DEA.

A review of 154 recent federal acquittals nationally found that 1 in 6 involved informant problems.

Because payments to informants can become an issue at trial, they are carefully monitored.

Informant expenditures are “watched so closely, agents aren’t allowed to pay an informant unless they have a witness,” said Dennis Fitzgerald, a former DEA agent and author of the new second edition of “Informants, Cooperating Witnesses, and Undercover Investigations: A Practical Guide to Law, Policy and Procedure.”

DEA offices must get approval from upper management before paying an informant more than $100,000 in one year, or $200,000 over multiple years.

The Office of the Inspector General found in 2005 that the DEA wasn’t following the rules. The agency’s “unreliable” database wasn’t totaling payments to the same informant from different offices or varied funding sources. The DEA’s Confidential Source Unit didn’t communicate well with its Office of Finance.

The inspectors made 12 recommendations to improve a “lax internal control environment where payments may be approved that are not reasonable, appropriate, or justified.”

‘Money squirting’

Now, according to a posting on the Office of the Inspector General’s website, inspectors are looking into “the DEA’s management and oversight of its Confidential Source Program, including compliance with rules and regulations associated with the use of confidential sources, and oversight of payments to confidential sources.” The office’s counsel wouldn’t detail the probe.

Experts said it would be surprising if the DEA completely ignored the 2005 report.

“The president of the United States puts you in charge of this program, and you find out that you’ve got all of this money squirting out from these various pots and it’s a substantial amount of money, and nobody is keeping an eye on it,” said Scott Lilly, a senior fellow with the Center for American Progress and former staff director for the House Appropriations Committee, who retired from government in 2004. “Wouldn’t that scare the hell out of you?”

The Post-Gazette, citing FOIA, asked for the DEA’s accounting policy for payments to informants. The agency provided a two-page policy, with 13 redactions encompassing well over half of the document. The DEA claimed that the release of unredacted accounting rules would “disclose techniques” and could “risk circumvention of the law.”

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, by contrast, released a 10-page, unredacted policy governing payments to informants. The U.S. Marshals Service provided a 15-page policy, with one phrase redacted.

Bucking trends

The DEA’s overall budget increased 3 percent from 2010 to 2014, to $2.88 billion. But its spending on informants, according to the Justice Department, jumped by one-third.

The agency paid informants $24.7 million in fiscal 2010, upward of $29 million in each of the following three years, and $33.1 million last year.

“That sounds like a lot of money to me,” Mr. Lilly said.

“If I were betraying the confidence of a drug lord,” he added, “I’d probably want a lot of money to offset the risk.”

Some other agencies have scaled back their spending on informants. The Marshals Service, for instance, paid its informants a total of around $900,000 in 2010 and 2011 but that amount decreased to $600,000 in each of the past three years. The ATF has paid informants between $4.2 million and $4.5 million in each of the past five years.

“The DEA often depends on informants that deal with, say, the cartels in Mexico, other cartels around the world,” noted Alberto Gonzales, who oversaw the Justice Department as attorney general from 2005 to 2007 and is dean of the Belmont University College of Law in Nashville, Tenn.

The FBI has not yet complied with an FOIA request of December 2013, asking for a description of all of its spending on informants, saying it will try to address it by September. Last year, the bureau used $7.2 million in Asset Forfeiture Program proceeds to reward informants, but the full extent of its spending on sources has not been released.

Global hand search

Fifteen months ago, the Post-Gazette asked the DEA to disclose any budgets or other documents describing payments to confidential informants for the years 2010 through 2014, plus breakdowns by geographic district, and itemizations of awards that are based on percentages of assets seized. The newspaper recognized that sensitive material could be redacted.

The DEA said in February 2014 that release of informant budgets would “constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy” and declined to search for documents.

On appeal, the DEA wrote that to answer the request, it would have to coordinate “approximately 222 individual DEA domestic offices … as well as approximately 86 DEA foreign offices and a number of DEA Headquarters offices.”

Though it has a payment database, the DEA claimed that answering the FOIA request would take “an estimated 24,240 or more man hours, conducting hand searches to compile the information.” That breaks down to two employees for two solid weeks in each of the 308 offices.That estimate “seems exorbitant,” said Ginger McCall, director of the Open Government Project at the Electronic Privacy Information Center in Washington, D.C. “It’s a large amount of time to locate a file that they really should have readily available.”

The Office of Information Policy concluded that the DEA “does not maintain the type of records” sought and upheld the denial. Last week, the Justice Department released year-by-year spending totals but not details.

Mr. Gonzales was not surprised that the agency didn’t want to detail its informant program.

“You don’t want to hit [the cartels] over the head with this information, oh my gosh, the U.S. is paying this much for informants,” the former attorney general said. “The more we talk about what we do to gather up information to protect America, the smarter our enemy gets. They change tactics.”

Ms. McCall, an FOIA lawyer, said America’s foes should not be an excuse to keep spending secret. “These sorts of nebulous ‘it’s going to help our enemies and it’s going to help criminals’ arguments are not sufficient.”

Filed under: General Problems

Ops, I meant CBS.

CBC just reported that a former DEA informant wants to quit, he is over 60, and wants to live in the USA but the government won’t let him. Shame on the government. He was the number one guy to go to for over 20 years and helped in bringing down the South American cartels.